Irrational Exuberance for 04/08/2020

Hi folks,

This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email.

Posts from this week:

-

Staying aligned with authority.

-

Build versus buy.

-

Poking around Contentful.

Staying aligned with authority.

This is a draft guide for staffeng.com

It’s a common misconception that authority makes you powerful. Many folks aspiring towards more senior roles assume they’ll finally get to do things their way. They believe that the title inherently creates flexibility and autonomy. They believe that the friction holding them back will burst into a whirl of butterflies that scatter into the wind.

The reality is a bit more nuanced.

Titles come with the sort of power called organizational authority, and that variety of authority is loaned to you by a greater organizational authority. What’s bestowed can also be retracted, and retaining organizational authority depends on remaining deeply aligned with the bestowing sponsor, generally your direct manager. To remain effective within a staff-plus role, you have to learn the art of staying aligned with organizational authority.

Beyond the safety net

When asked for advice on entering a Staff-plus role, Duretti Hirpa shared, “Staff engineering is a completely different job. It’s no longer about your technical expertise. The job isn’t “computer” anymore, as I’m fond of saying. You’re now an agent of the organization.”

The golden rule of being an agent of the organization is that you must stay aligned with your organizational authority. Retire any remaining expectations that the company is designed to set you up for success. Now you are one of the people responsible for setting the company, your team and your manager up for success.

Most mature technology companies succeed in creating a predictable promotion pipeline from folks joining early in their careers up through attaining the Senior Engineer title. The process of getting a Staff Title is generally more complex than preceding titles, but usually navigated with the support of your engineering manager. Throughout this pipeline, you may become comfortable with your manager guiding your development and providing a safety net for your continued success. After reaching a Staff role, your safety net will cease to exist, or at best the safety net will be short enough that you’re quite capable of jumping past it and into the awaiting chasm. This will be increasingly true as you go further into Senior Staff and Distinguished Engineer roles.

Staff-plus roles are leadership roles, and in leadership roles the support system that got you here will fade away. Often abruptly, you’re now expected to align the pieces around you for own success.

Serving at the pleasure of the President

When Rick Boone described his role as Strategic Advisor to the Vice-President of Infrastructure at Uber, he compared his role to Hand of the King in Game of Thrones, and Leo McGarry from The West Wing who frequently remarked, “I serve at the pleasure of the President.” In both those examples, authority flows from the tight association with a greater authority, and it’s a great mental model for operating in a Staff-plus role. This can be a difficult transition from previous roles where your authority primarily accumulated through your personal actions and impact over time.

If you and your manager have worked together for years, then often you’ve already performed a subtle, subterranean sort of alignment over time. In other cases, a new executive will join who is familiar with supporting these roles, and will bring a deliberate map to how they want to work together. However, both of those circumstances are largely out of your control, so it’s valuable to develop your own approach to aligning upward with your manager.

To align with your manager, some areas to focus on are:

- Never surprise your manager. Nothing destroys trust faster than surprising your manager. Steering a large organization often involves juggling a number of people, projects and problems in your head at once, and surprises threaten the juggler’s rhythm. Large or frequent surprises also call into question whether a leader is truly taking responsibility for their organization. In general, treat each time you surprise your manager as an incident to be learned from and endeavor to prevent repeats.

- Don’t let your sponsor surprise you. Most folks have extremely high expectations of their managers, assuming for example that they will always remember to relay information relevant to your current work. Managers try to do this, some of them are excellent at it, and others are not particularly good. If your manager isn’t great at this, you should certainly give them feedback, but you should also take proactive action to facilitate information flow. This might be weekly email updates or a Slack thread within your team’s channel sharing your focuses for the week. During 1:1s, dig for feedback! Ask if there are other areas you should be focused on, and how your current priorities align with your manager’s. If you continue to surprise each other, then identify the controls you’ll use to partner together.

- Feed your manager context. If the first step is avoiding personally surprising your manager, the next step is to help your manager not get surprised by the wide organization. If teams are frustrated by a new policy or your internal tools aren’t scaling with needs, proactively feed that to your manager. Be clear that you’re not bringing them a problem to solve, rather conveying information you believe will be useful. Opinions are helpful, but even more helpful is data when you can find it.

Sometimes you’ll hear someone disparage a colleague saying that they’re excellent at “managing up.” There are certainly destructive ways to manage up where someone controls information to hide problems or misrepresent circumstances, but at its core managing up is about increasing bandwidth and reducing friction between you and your manager. Cultivating a deliberate partnership with your manager will go far further than practicing disappointment when they don’t meet your expectations.

Influencing without too much friction

Part of growing as a leader is developing your own perspective on how the world should work, and you can’t reach the Staff-plus level without that perspective. Having a clear sense of how things ought to work sharpens your judgement and enables you to act proactively, As you reach this next step of leadership, you increasingly have to merge your vision with those held by more senior organizational leaders.

Your first approach to solving this problem might be replacing your vision with another leader’s vision, and that approach works for some, but for many it means stepping away from the perspective that facilitated their success as a proactive leader with strong judgement. Instead, I recommend sharpening your awareness of the value distinctions between those that you hold and those that the organization operates under, and find a way to advocate for them without getting kicked out of the room.

People can only change so quickly, and organizations are made of people. If you’re deliberate in your approach, you’ll be able to influence your organization leaders immensely over time, but you’ll only get that time if you learn to remain in tight alignment at each step along the way.

Build versus buy.

A few years ago I was working on a contract negotiation with Splunk, and we kept running into what felt like a pretty unreasonable pricing structure. They wanted some number of millions of dollars for a three year license, which felt like a high price to pay for thirty-two ascii characters in a particular sequence. Even with the license, we'd still be the ones operating it and paying for the capacity to run it.

We decided to negotiate by calculating the cost of running our own ELK Stack cluster, determined by means of the appropriate solution of solid numbers and hand waving. We used this calculation to establish Splunk's value to us and ultimately got Splunk to come down to our calculated value instead of their fee structure, although I suspect we might have overpriced the value a bit and landed too high within the zone of possible agreement.

Recently Calm has been considering if we should move parts of our workflow to a headless CMSes, and consequently I've been thinking a bit more about how to make these sorts of build versus buy decisions, and in particular how to evaluate the "buy" aspect. Ultimately, I think it comes down to risk, value, and cost.

Risk

Using a vendor is taking on an outstanding debt. You know you will have to service that debt's interest over time, and there's a small chance that they might call the debt due at any point.

From a risk perspective, calling the debt due isn't the vendor holding you hostage for a huge sum, although certainly if there's little competition the risk of price increases is real. Rather, the most severe risks are the vendor going out of business, shifting their pricing in a way that's incompatible with your usage, suffering a severe security breach that makes you decide to stop working with them, or canceling the business line (which some claim has undermined Google's abiltiy to gain traction on new platforms).

Some risks can be managed through legal contracts. Other risks can be managed by purchasing insurance. Other sorts you simply have to decide whether they're acceptable.

In the build versus buy decision, most companies put the majority of their energy into identifying risk, which has its place, but often culminates in a robust not invented here culture that robs the core business of attention. To avoid that fate, it's important to spend at least as much time on the value that comes from buy decisions.

Value

Businesses succeed by selling something useful to their users. Work directly towards that end is core work, and all other work is auxiliary work. Well-run, efficiency-minded businesses generally allocate just enough resources to auxiliary work to avoid bottlenecks in their core work, reserving the majority of their resources for core work. This efficiency-obsession is a subtle mistake, because it treats auxiliary work as cost centers disconnected from value creation.

In reality, value is created by the overall system, which includes auxiliary work. Many companies create more value from their auxiliary work than their core work, for example a so-so product supported by extraordinary marketing efforts. Other companies sabotage their core work by underinvesting in the auxiliaries, for example a company of engineers eternally awaiting design guidance.

To calculate the value of a vendor, compare the vendor's offering against what you're willing to build today. The perfected internal tool will always be better than the vendor's current offering, but you're not going to build the perfected internal tool right now, what will you actually build?

Also, how will the quality and capabilities of the two approaches diverge over time? Most companies, particularly small ones, simply can't rationally invest into improving their internal tools, such that they get worse over time relative to an active vendor. If you're assuming the opposite, dig into those assumptions a bit. Vendors selling those internal tool have a totally different incentive structure than you do, and it's an incentive structure that requires they make ongoing investments in their offering.

At a certain point you may reach your own internal economies of scale that support ongoing investment into internal tooling. Uber famously built their own replacement for both Greenhouse and Zendesk after reaching about 2,000 engineers, but they relied on vendors extensively up until they reached that point.

One way that folks sometimes discount vendors' value to zero is they worry that the vendor simply won't be good enough to use at all. This implies the existence of a boolean cutoff in quality between sufficient and insufficient quality. This is a rigid mindset that doesn't reflect reality: quality is not boolean. There will be gaps in vendor functionality, and you should absolutely identify those gaps and understand the cost of addressing them, but avoid falling into a mindset that your requirements are fixed absolutes.

When it comes to build versus buy, the frequently repeated but rarely followed wisdom is good advice: if you're a technology company, vendors usually generate significant value if they're outside your company's core competency; within your core competency, they generally slow you down.

Cost

Once you understand the value a vendor can bring, you then have to consider the costs. The key costs to consider are: integration, financial, operating and evolution.

Integration costs are your upfront costs before the vendor can start creating value. This is also the cost of replacing the vendor if the current vendor were to cease to exist at some point in the future. This is where most vendor discussions spend the majority of their time.

Financial costs are how much the contract costs, including projecting utilization over time to understand future costs. This is another area that usually gets a great deal of attention during vendor selection processes, but often with a bit too much emphasis on cost-cutting and not enough on value.

Operating costs are the cost of using the vendor, and in my experience are rarely fully considered. This includes things like vendor outages or degradations, as well as more nuanced issues like making mandatory integration upgrades as the vendor evolves their platform. Stripe's Payment Intents API is far more powerful than the previous Charge API, but there's a large gap between knowing a more powerful solution is available and learning last year that PSD2's SCA requirements meant you had to upgrade to keep selling to buyers in the European Union.

How you want to use a vendor will shift over time, which makes evolution costs essential to consider, and similar to operating costs are an oft neglected consideration. This is where vendor architecture matters a great deal, and well-designed vendors shine. An example of good vendor architecture is headless CMSes: they're flexible because they're focused on facilitating one piece of the workflow. If some piece of the workflow doesn't fit for a niche workflow you support, just cut that one piece away from the headless CMS: you don't have to replace the entire thing at once.

Some vendor solutions try to create a crushing gravity that restricts efforts to move any component outside their ecosystem, and these are the vendors to avoid. Folks often focus on things like being vendor-agnostic, e.g. the ability to wholesail migrate from one vendor to another, when I think it's usually more valuable to focus on being vendor-flexible: being able to move a subset of your work to a better suited tool.

Your total cost model should incorporate all of these costs, and becomes a particularly powerful tool in negotiating the contract.

Pulling it all together

Once you've thought through the value, risk and cost, then at some point you have to make a decision. My rule of thumb is to first understand if there are any sufficiently high risks that you simply can't move forward. If the risks are acceptable, then perform a simple value versus cost calculation and accept the results!

Generally the two recurring themes I've seen derail this blindingly obvious approach are legal review (outsized emphasis on unlikely or mitigatable risks) and unfungible budgets (overall cheaper to use vendor, but company views headcount budget and vendor budgets as wholy distinct).

These are both sorts of bureaucratic scar tissue that accumulate from previous misteps, and aim to protect the business. On average, they likely are creating the right outcomes for the company, but for specific decisions they might not be. If you believe strongly enough that this is one of those exceptions, then ultimately I've found you need an executive sponsor to push it through.

A note on vendor management

Throwing in one more thought before wrapping this up, I've found that many companies are quite bad at vendor management and are quite good at building things. As such, their calculations always show that vendors are worse than building it themselves, and that's probably true for them in their current state.

To get the full value from vendors, you have to invest in managing vendors well. A company that does this extraordinarily well is Amazon, who issue their vendors quarterly report cards grading their performance against the contract and expectations. Getting great results from vendors requires managing them. If you neglect them and get bad results, that's on you.

Poking around Contentful.

Slightly related to my notes on build versus buy decisions, I spent some time specifically getting a feel for Contentful over the weekend, and have written up some notes here.

Why Headless CMSes?

There are a lot of headless CMSes out there, the one I've personally used most is Airtable. You could argue Airtable isn't just a headless CMS, and sure, that's a fine argument to make. As a category, I think headless CMSes do a bunch of things particularly well:

- There are many of them, so it's unlikely you'll find your vendor shutting down without a "good enough" replacement to migrate to

- Content management workflows are dynamic living things that change frequently, but generally it's the steps in the process, not the representation of the process, that is the core competency. Offloading this to a flexible tool that is extensible without engineering investment is a big enabler for the teams operating the workflow and allows engineers to spend more energy on highest leverage work.

- Because they're headless, you own last mile delivery. This allows you to retain control of quality, latency and reliability. It also reduces switching costs, because you won't require your users to perform a migration to a new URL, tool or whatnot. It further reduces switching costs because they require decoupling the last-mile from the workflow.

- That same decoupling also means you can perform a incremental migration towards or away from the CMS, allowing you to move simple functionality early when you start migrating, and also to move your most sophisticated workflows onto custom tooling if/when you get around to building them.

- The kind of content you store in a CMS is rarely sensitive. It's usually marketing content or related to a content creation pipeline (say, articles for a magazine). This limits your exposure to risk from a security or privacy breach since you wouldn't have user data there anyway.

Onboarding

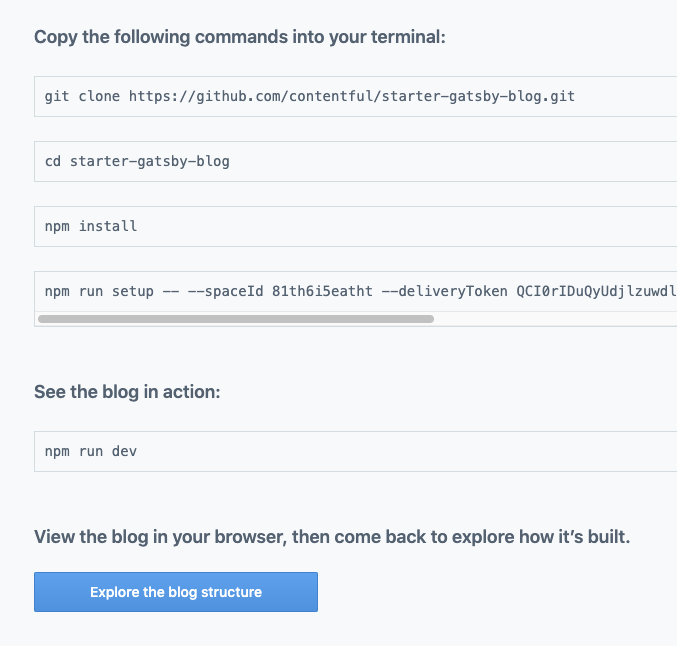

Before going further, obligatory mention that I've already deleted the referenced API keys here!

I got started with Contentful by creating a new account and going through their signup and onboarding workflow.

I was pleasantly surprised at how well integrated their onboarding was, promising four easy steps:

git clone https://github.com/contentful/starter-gatsby-blog.git

cd starter-gatsby-blog

npm install

npm run setup – \

–spaceId etc \

–deliveryToken etc \

–managementToken etc

However, I must admit that I ran into a couple of issues along the way of following the tutorial. Most of these are specific to my local environment which is certainly my fault, but my experience was that the onboarding focused on the happy integration path to the exclusion of addressing problems that could arise along the way.

First, the deprecation warnings within their repository were a bit offsetting.

Because you're generating a static site with Gatsby, I realize that the threat vectors here are fairly minimal, but it highlights to me the ongoing costs of maintaining these sorts of integrations well.

Second, my home computer had an old version of Nodejs running, and it failed with a fairly unhelpful error:

/Users/will/git/starter-gatsby-blog/node_modules/@hapi/joi/lib/types/object/index.js:255

!pattern.schema._validate(key, state, { ...options, abortEarly:true }).errors) {

SyntaxError: Unexpected token ...

Nothing about the error explicitly referenced it being out of date, but I just sort of assumed it was based on previous debugging experience and the fact that it was failing to lex modern JavaScript syntax, so I brew installed the latest version

brew upgrade nodejs

This sparked a bit of a side-quest to upgrade Node because my Homebrew install apparently broke in my last OS upgrade, but things worked out after some poking around.

After upgrading I finally ran npm run dev and got an error

about my spaceId not being set.

TypeError: Cannot read property 'spaceId' of undefined

I assumed this was due to running setup before the version ugprade, so

reran the npm run setup command from earlier, then I realized it was

a disaster all the way down and deleted node_modules/ and started over.

Then it failed again with a different error, and I deleted

package-lock.json, yarn.lock and node_modules/ and reinstalled from

scratch, and

that did do the trick, although I did hit a rate limiting error:

12:07:08 - Rate limit error occurred. Waiting for 1532 ms before retrying...

The import was successful.

I'm not sure if that ratelimit did anything. seemingly it was successful so I'm assuming not. Their installation focused very heavily on SDKs, going so far as not to mention or reference their direct HTTP APIs.

I'm a strong believer that SDKs are the modern 3rd-party API interface that will replace HTTP/JSON and gRPC interfaces, but I think it's still a bit messy to not include a link to the underlying interface. It's often much easier to understand the API's data model and integration flow from the API spec than the SDK, and it is the fallback point for unsupported languages (in this case, Go was the language I noticed missing for my interests).

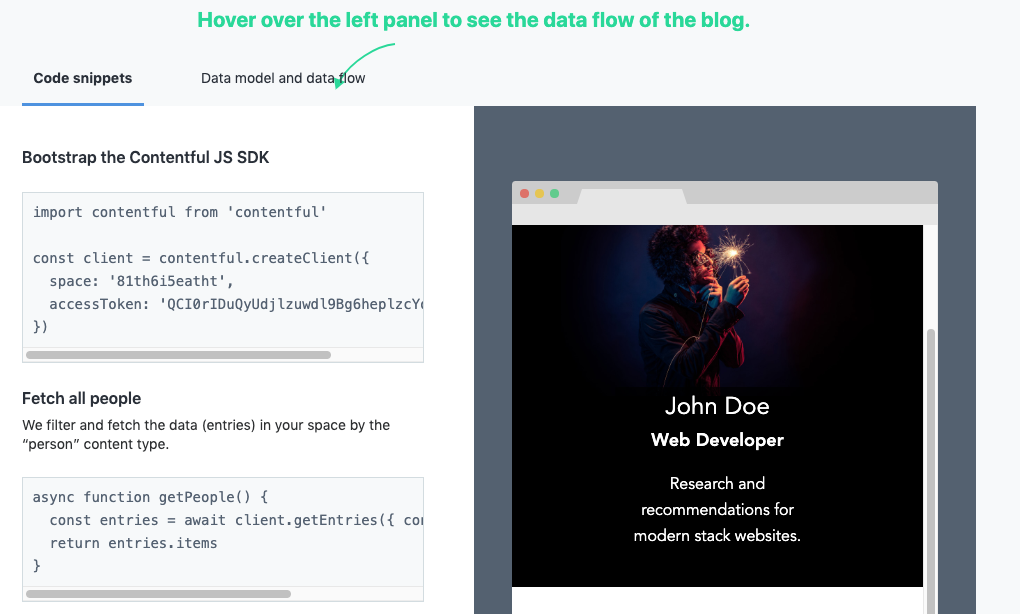

Anyway, API document griping aside, next came to their very helpful step-by-step explanation of how the Gatsby example integrates witih their SDK and API.

It's all pretty straight forward, essentially exporting all the Contentful data using your space and access token.

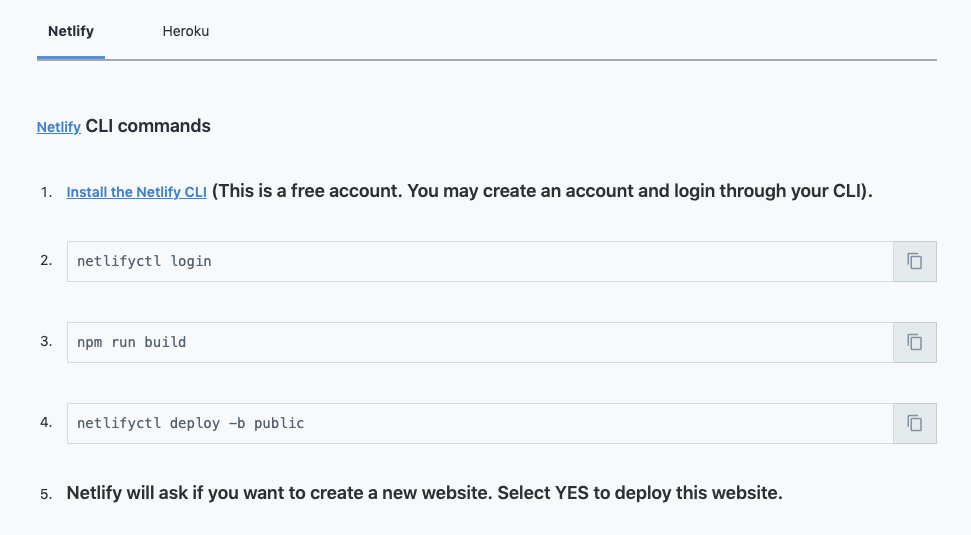

Next it brought us to a deployment page for the sample app, asking us to use either Netlify or Heroku.

Netlify resonated as a hip up and coming deployment target, and Heroku is a wonderful platform, but it felt a bit odd that none of AWS, Alicloud, Azure, or Google Cloud got instructions. Perhaps the assumption is that folks operating on those platform will be able to figure it out, but I think the same is true for folks on Netlify or Heroku, and most folks are on large cloud providers.

That said, figuring it out for AWS and GCP should be relatively simply, you build the Gatsby site via

./node_modules/.bin/gatsby build

Then move public/ onto Firebase Hosting

or Amazon S3.

Either way, at this point I was done with the initial tutorial.

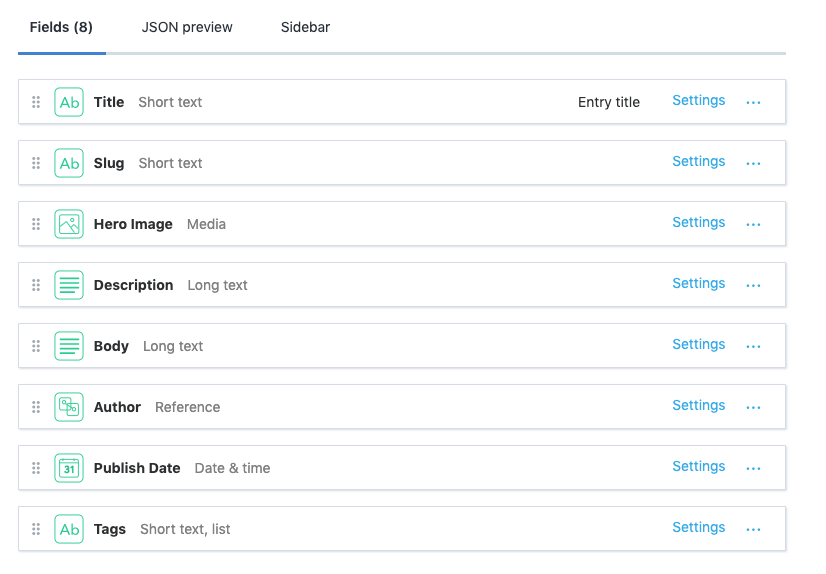

Data models

Contentful allows you to make different data models, which are essentially a database schema or spreadsheet headers for a certain type of content.

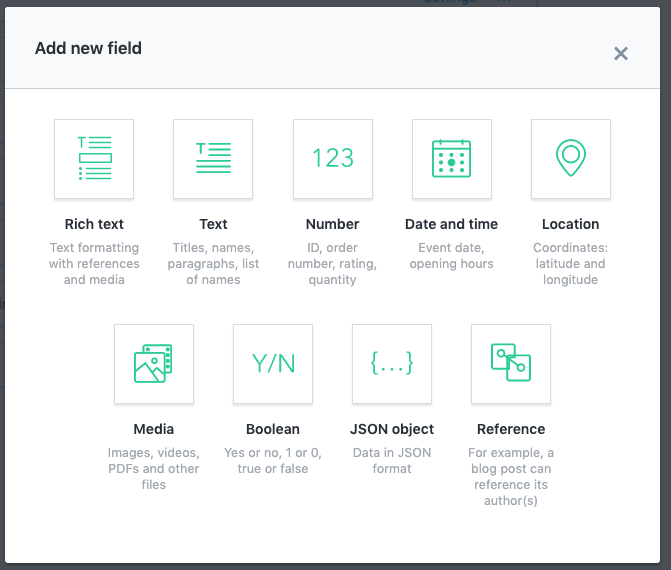

You can create a number of different types of fields, including the much maligned JSON object.

Altogether, this feels like a very reasonable set of fields and data modeling capabilities for a CMS. There are certainly other types you could imagine wanting, but the ones they support are sufficiently general that I think you could model whatever you need fairly easily.

Workflow

The final thing I wanted to do was spend some time getting familiar with the workflow to create and edit content.

As someone who has created three or four versions of my own CMS for lethain.com and now staffeng.com, I appreciate many of the little touches. For example, scheduling a publish date in the future is delightful, and the combination of future publishing and webhooks is a clever interface to decouple content creators and engineers while still getting the right functionality.

The editing itself seemed reasonable, especially if you setup the content preview integration.

However, I do find the available workflow to be a bit simpler than I'd expect from an enterprise grade CMS. A typical workflow I'd imagine is something getting drafted, then peer reviewed, then have an editor review, then deploy it out. You can do parts of this, for example only allowing editors the permissions to "publish" content, but it's fairly constrained and more importantly doesn't facilitate the easy handoffs across each step in your workflow.

I imagine you'd end up doing something along the lines of create a workflow content type, adding a reference to the workflow stages in your content, and integrate with webhooks to notify the appropriate folks based on the stage it entered, but that feels a bit awkward to ask each user to model and integrate for what I imagine is a fairly common feature request.

Compared to Airtable

As a long-term user of Airtable, it was interesting to play around with a more focused headless CMS solution. Airtable has a blog post of how to make it a headless CMS with Gatsby, but in many ways I think Airtable struggles to explain itself. Wikipedia struggles to describe it too, claiming it's a spreadsheet-database hybrid, with features of a database but applied to a spreadsheet.

Altogether, I really enjoyed poking around with Contentful a bit, and can definitely see how it could be a powerful toolkit for folks to build on.

That's all for now! Hope to hear your thoughts on Twitter at @lethain!

|